1988 United States presidential election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

538 members of the Electoral College 270 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 52.8%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

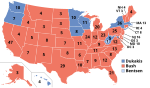

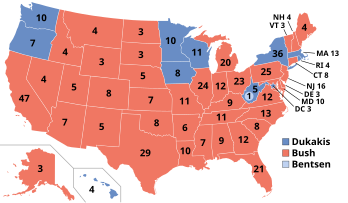

Presidential election results map. Red denotes states won by Bush/Quayle and blue denotes those won by Dukakis/Bentsen. Light blue is the electoral vote for Bentsen/Dukakis by a West Virginia faithless elector. Numbers indicate electoral votes cast by each state and the District of Columbia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 8, 1988. The Republican Party's ticket of incumbent Vice President George H. W. Bush and Indiana senator Dan Quayle defeated the Democratic ticket of Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis and Texas senator Lloyd Bentsen.

The election was the third consecutive and most recent landslide victory for the Republican Party. It remains the most recent election in which a candidate won over 400 electoral votes, as well as 40 or more states.[2] Conversely, it began an ongoing streak of presidential elections that were decided by a single-digit popular vote margin.[3] It was the first time since 1948, the first time for the Republicans since 1928, and the most recent presidential election in which a party won more than two consecutive presidential terms. Additionally, it was the last time that the Republicans won the popular vote in consecutive elections, and the last that a Republican who had not already served as president won the popular vote. This remains the most recent presidential election in which the incumbent vice president was elected president, which had last occurred in 1836, though Joe Biden was elected in 2020 as a former vice president.

President Ronald Reagan was ineligible to seek a third term because of the 22nd Amendment. Instead, Bush entered the Republican primaries as the frontrunner, defeating Kansas Senator Bob Dole and televangelist Pat Robertson. He selected Indiana Senator Dan Quayle as his running mate. Dukakis won the Democratic primaries after Democratic leaders Gary Hart and Ted Kennedy withdrew or declined to run. He selected Texas Senator Lloyd Bentsen as his running mate. It was the first election since 1968 to lack an incumbent president on the ballot. Reagan was also the first incumbent president since Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1960 to be barred from seeking reelection.

Bush ran an aggressive campaign that concentrated mainly on the strong economy, reduction in crime, and continuance with Reagan's policies. He attacked Dukakis as an elitist "Massachusetts liberal", to which Dukakis ineffectively responded. Despite Dukakis initially leading in the polls, Bush pulled ahead after the Republican National Convention and extended his lead after two strong debate performances. Bush won a decisive victory over Dukakis, winning the Electoral College and the popular vote by sizable margins.

Bush became the first sitting vice president to be elected president since Martin Van Buren in 1836, and the first vice president to be elected president since Richard Nixon (as former vice president) in 1968. This remains the last time that a Republican has carried California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maine,[b] Maryland, New Jersey, and Vermont. Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Tennessee would not vote Republican again until 2000, while New Mexico would not vote Republican again until 2004. Michigan and Pennsylvania would not vote Republican again until 2016.

This remains the most recent presidential election in which the Democratic nominee did not win at least 200 electoral votes. As of 2024, this is also the most recent presidential election in which the Republican nominee won the female vote; as well as the last presidential election in which the Rust Belt states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin did not vote for the same candidate.[4]

Since the death of Jimmy Carter in 2024, this is the earliest election where at least one of the major party nominees for president (Dukakis) or vice president (Quayle) is still alive (Bentsen died in 2006 and Bush died in 2018).

Republican Party nomination

[edit]Republican candidates

[edit]- George H. W. Bush, incumbent Vice President from Texas[5]

- Bob Dole, U.S. senator from Kansas[6]

- Pat Robertson, televangelist from Virginia[7]

- Jack Kemp, U.S. representative from New York[8]

- Pete du Pont, former governor of Delaware[9]

- Alexander Haig, former secretary of state, from Pennsylvania[10]

- Ben Fernandez, former Special Ambassador to Paraguay, from California[11]

- Paul Laxalt, former U.S. senator from Nevada[12]

- Donald Rumsfeld, former Secretary of Defense from Illinois[13]

- Harold Stassen, former Governor of Minnesota[14]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| George H. W. Bush | Dan Quayle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 43rd Vice President of the United States (1981–1989) |

U.S. Senator from Indiana (1981–1989) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While Bush had long been seen as Reagan's natural successor, there was still a degree of opposition within the party to his candidacy. Historical precedent was not seen to favor Bush's chances, as no incumbent vice president had been elected as president since Martin Van Buren in 1836. Dole attracted support among those who were concerned that Bush, whose electoral experience outside of his campaigns with Reagan was limited to running unsuccessfully for the Senate and twice successfully for the House of Representatives in the 1960s, had not done enough to establish himself as a candidate in his own right. Others who wished to further continue the shift towards social conservatism that had begun during Reagan's presidency supported Robertson.[citation needed]

Bush unexpectedly came in third in the Iowa caucus, which he had won in 1980, behind Dole and Robertson. Dole was also leading in the polls of the New Hampshire primary, and the Bush camp responded by running television commercials portraying Dole as a tax raiser, while Governor John H. Sununu campaigned for Bush. Dole did nothing to counter these ads and Bush won, thereby gaining crucial momentum, which he called "Big Mo".[15] Once the multiple-state primaries such as Super Tuesday began, Bush's organizational strength and fundraising lead were impossible for the other candidates to match, and the nomination was his.

The Republican Party convention was held in New Orleans, Louisiana. Bush was nominated unanimously and selected U.S. Senator Dan Quayle from Indiana as his running mate. In his acceptance speech, Bush made the pledge "Read my lips: No new taxes," which contributed to his loss in the 1992 election.

Democratic Party nomination

[edit] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Michael Dukakis | Lloyd Bentsen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 65th and 67th Governor of Massachusetts (1975–1979, 1983–1991) |

U.S. Senator from Texas (1971–1993) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Candidates in this section are sorted by date of withdrawal from the primaries | ||||||||

| Jesse Jackson | Al Gore | Paul Simon | Dick Gephardt | Gary Hart | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| President of the Rainbow Coalition from South Carolina (1983–present) |

U.S. Senator from Tennessee (1985–1993) |

U.S. Senator from Illinois (1985–1997) |

U.S. Representative from Missouri (1977–2005) |

U.S. Senator from Colorado (1975–1987) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | ||||

| LN: July 20, 1988 E: July 30, 1988 6,788,991 votes 1,023 PD |

S: April 21, 1988 E: June 16, 1988 3,185,806 votes 374 PD |

S: April 7, 1988 E: June 8, 1988 1,082,960 votes 161 PD |

W: March 28, 1988 E: June 8, 1988 1,399,041 votes 137 PD |

W: March 11, 1988 415,716 votes | ||||

| [16] | [17] | [18][19] | [18][19] | |||||

| Bruce Babbitt | James Traficant | Patricia Schroeder | Joe Biden | |||||

|

|

|

| |||||

| Fmr. Governor of Arizona (1978–1987) |

U.S. Representative from Ohio (1985–2002) |

U.S. Representative from Colorado (1973–1997) |

U.S. Senator from Delaware (1973–2009) | |||||

| Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | ||||||

| W: February 18, 1988 E: June 8, 1988 77,780 votes |

?: After January 26, 1988 | W: September 28, 1987 | W: September 23, 1987 E: June 22, 1988 | |||||

| [18][19] | [20][21][22][23] | [24] | ||||||

In the 1984 presidential election the Democrats had nominated Walter Mondale, a traditional New Deal-type liberal, who advocated for those constituencies that Franklin Roosevelt forged into a majority coalition,[25] as their candidate. When Mondale was defeated in a landslide, party leaders became eager to find a new approach to get away from the 1980 and 1984 debacles. After Bush's image was affected by his involvement on the Iran-Contra scandal much more than Reagan's, and after the Democrats won back control of the U.S. Senate in the 1986 congressional elections following an economic downturn, the party's leaders felt optimistic about having a closer race with the GOP in 1988, although probabilities of winning the presidency were still marginal given the climate of prosperity.

One goal of the party was to find a new, fresh candidate who could move beyond the traditional New Deal-Great Society ideas of the past and offer a new image of the Democrats to the public. To this end party leaders tried to recruit New York Governor Mario Cuomo to be a candidate. Cuomo had impressed many Democrats with his keynote speech at the 1984 Democratic Convention, and they believed he would be a strong candidate.[26] After Cuomo chose not to run, the Democratic frontrunner for most of 1987 was former Colorado Senator Gary Hart.[27] He had made a strong showing in the 1984 presidential primaries and, after Mondale's defeat, had positioned himself as the moderate centrist many Democrats felt their party would need to win.[28]

But questions and rumors about extramarital affairs and past debts dogged Hart's campaign.[29] Hart had told New York Times reporters who questioned him about these rumors that, if they followed him around, they would "be bored". In a separate investigation, the Miami Herald had received an anonymous tip from a friend of Donna Rice that Rice was involved with Hart. After his affair emerged, the Herald reporters found Hart's quote in a pre-print of The New York Times magazine.[30] After the Herald's findings were publicized, many other media outlets picked up the story and Hart's ratings in the polls plummeted. On May 8, 1987, a week after the Rice story broke, Hart dropped out of the race.[29] His campaign chair, Representative Patricia Schroeder, tested the waters for about four months after Hart's withdrawal, but decided in September 1987 that she would not run.[31] In December 1987, Hart surprised many pundits by resuming his campaign,[32] but the allegations of adultery had delivered a fatal blow to his candidacy, and he did poorly in the primaries before dropping out again.[33]

Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts had been considered a potential candidate, but he ruled himself out of the race in the fall of 1985. Two other politicians mentioned as possible candidates, both from Arkansas, did not join the race: Senator Dale Bumpers and Governor and future President Bill Clinton.

Joe Biden's campaign also ended in controversy after he was accused of plagiarizing a speech by Neil Kinnock, then-leader of the British Labour Party.[34] The Dukakis campaign secretly released a video in which Biden was filmed repeating a Kinnock stump speech with only minor modifications.[35] Biden later called his failure to attribute the quotes an oversight, and in related proceedings the Delaware Supreme Court's Board on Professional Responsibility cleared him of a separate plagiarism charge, leveled for plagiarizing an article during his law school.[36] This ultimately led him to drop out of the race. Dukakis later revealed that his campaign had leaked the tape, and two members of his staff resigned. (Biden later ran twice more for the Democratic nomination, unsuccessfully in 2008 and successfully in 2020. He was elected the 47th vice president in 2008, serving two terms under President Barack Obama. In 2021, he became the 46th president, over 33 years after his first campaign for the office ended.)

Al Gore, a senator from Tennessee, also chose to run for the nomination. Turning 40 in 1988, he would have been the youngest man to contest the presidency on a major party ticket since William Jennings Bryan in 1896, and the youngest president ever if elected, younger than John F. Kennedy at election age and Theodore Roosevelt at age of assumption of office. He eventually became the 45th Vice President of the United States under Bill Clinton, then the Democratic presidential nominee in 2000, losing to George W. Bush, George H.W.'s son.

Primaries

[edit]After Hart withdrew from the race, no clear frontrunner emerged before the primaries and caucuses began. The Iowa caucus was won by Dick Gephardt, who had been sagging heavily in the polls until, three weeks before the vote, he began campaigning as a populist and his numbers surged. Illinois Senator Paul M. Simon finished a surprising second, and Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis finished third. In the New Hampshire primary, Dukakis came in first, Gephardt fell to second, and Simon came in third. In an effort to weaken Gephardt's candidacy, both Dukakis and Gore ran negative television ads against Gephardt. The ads convinced the United Auto Workers, which had endorsed Gephardt, to withdraw their endorsement; this crippled Gephardt, as he relied heavily on the support of labor unions.

In the Super Tuesday races, Dukakis won six primaries, to Gore's five, Jesse Jackson five and Gephardt one, with Gore and Jackson splitting the Southern states. The next week, Simon won Illinois with Jackson finishing second. Jackson captured 6.9 million votes and won 11 contests: seven primaries (Alabama, the District of Columbia, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Puerto Rico and Virginia) and four caucuses (Delaware, Michigan, South Carolina and Vermont). He also scored March victories in Alaska's caucuses and Texas's local conventions, despite losing the Texas primary. Briefly, after he won 55% of the vote in the Michigan Democratic caucus, he had more pledged delegates than all the other candidates.

Jackson's campaign suffered a significant setback less than two weeks later when he was defeated in the Wisconsin primary by Dukakis. Dukakis's win in New York and then in Pennsylvania effectively ended Jackson's hopes for the nomination.

Democratic Convention

[edit]The Democratic Party Convention was held in Atlanta, Georgia from July 18–21. Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton placed Dukakis's name in nomination, and delivered his speech, scheduled to be 15 minutes long, but lasting so long that some delegates began booing to get him to finish; he received great cheering when he said, "In closing...".[37][38]

Texas State Treasurer Ann Richards, who was elected the state governor two years later, gave a speech attacking George Bush, including the line "Poor George, he can't help it, he was born with a silver foot in his mouth."

With only Jackson remaining as an active candidate to oppose Dukakis, the tally for president was:

| Presidential ballot | Vice Presidential ballot | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Michael S. Dukakis | 2,876.25 | Lloyd M. Bentsen | 4,162 |

| Jesse L. Jackson | 1,218.5 | ||

| Richard H. Stallings | 3 | ||

| Joe Biden | 2 | ||

| Richard A. Gephardt | 2 | ||

| Gary W. Hart | 1 | ||

| Lloyd M. Bentsen | 1 |

Jackson's supporters said that since their candidate had finished in second place, he was entitled to the vice presidential nomination. Dukakis disagreed, and instead selected Senator Lloyd Bentsen from Texas. Bentsen's selection led many in the media to dub the ticket the "Boston-Austin" axis, and to compare it to the pairing of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson in the 1960 presidential campaign. Like Dukakis and Bentsen, Kennedy and Johnson were from Massachusetts and Texas respectively.

Other nominations

[edit]Libertarian Party

[edit]

Ron Paul and Andre Marrou formed the ticket for the Libertarian Party. Their campaign called for the adoption of a global policy on military nonintervention, advocated an end to the federal government's involvement with education, and criticized Reagan's "bailout" of the Soviet Union. Paul was a former member of the U.S. House of Representatives, first elected as a Republican from Texas in an April 1976 special election. He was known as an opponent of the war on drugs.[citation needed]

New Alliance Party

[edit]Lenora Fulani ran for the New Alliance Party, and focused on issues concerning unemployment, healthcare, and homelessness. The party had full ballot access, meaning Fulani and her running mate, Joyce Dattner, were the first pair of women to receive ballot access in all 50 states.[39] Fulani was the first African American to do so.[citation needed]

Socialist Party

[edit]Willa Kenoyer and Ron Ehrenreich ran for the Socialist Party, advocating a decentralist government approach with policies determined by the needs of the workers.[citation needed]

Populist Party

[edit]David E. Duke stood for the Populist Party. A former leader of the Louisiana Ku Klux Klan, he advocated a mixture of White nationalist and separatist policies with more traditionally conservative positions, such as opposition to most immigration from Latin America and to affirmative action. [1]

General election

[edit]Campaign

[edit]During the election, the Bush campaign sought to portray Dukakis as an unreasonable "Massachusetts liberal." Dukakis was attacked for such positions as opposing mandatory recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance in schools, and being a "card-carrying member of the ACLU" (a statement Dukakis made early in the primary campaign to appeal to liberal voters). Dukakis responded by saying that he was a "proud liberal" and that the phrase should not be a bad word in America.[citation needed]

Bush pledged to continue Reagan's policies, but also vowed a "kinder and gentler nation" in an attempt to win over more moderate voters. The duties delegated to him during Reagan's second term (mostly because of the President's advanced age, Reagan turning 78 just after he left office) gave him an unusually high level of experience for a vice president.

A graduate of Yale University, Bush derided Dukakis for having "foreign-policy views born in Harvard Yard's boutique."[40] New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd asked, "Wasn't this a case of the pot calling the kettle elite?" Bush said that, unlike Harvard, Yale's reputation was "so diffuse, there isn't a symbol, I don't think, in the Yale situation, any symbolism in it... Harvard boutique to me has the connotation of liberalism and elitism," and said he intended Harvard to represent "a philosophical enclave", not a statement about class.[41] Columnist Russell Baker wrote, "Voters inclined to loathe and fear elite Ivy League schools rarely make fine distinctions between Yale and Harvard. All they know is that both are full of rich, fancy, stuck-up and possibly dangerous intellectuals who never sit down to supper in their undershirt no matter how hot the weather gets."[42]

Dukakis was badly damaged by the Republicans' campaign commercials, including "Boston Harbor",[43] which attacked his failure to clean up environmental pollution in the harbor, and especially by two commercials that were accused of being racially charged, "Revolving Door" and "Weekend Passes" (also known as "Willie Horton"),[44] that portrayed him as soft on crime. Dukakis was a strong supporter of Massachusetts's prison furlough program, which had begun before he was governor. As governor, Dukakis vetoed a 1976 plan to bar inmates convicted of first-degree murder from the furlough program. In 1986, the program had resulted in the release of convicted murderer Willie Horton, an African American man who committed a rape and assault in Maryland while out on furlough.

A number of false rumors about Dukakis were reported in the media, including Idaho Republican Senator Steve Symms's claim that Dukakis's wife Kitty had burned an American flag to protest the Vietnam War,[45] as well as the claim that Dukakis himself had been treated for mental illness.[46]

"Dukakis in the tank"

[edit]

Dukakis attempted to quell criticism that he was ignorant on military matters by staging a photo op in which he rode in an M1 Abrams tank outside a General Dynamics plant in Sterling Heights, Michigan.[47] The move ended up being regarded as a major public relations blunder, with many mocking Dukakis's appearance as he waved to the crowd from the tank. The Bush campaign used the footage in an attack ad, accompanied by a rolling text listing Dukakis's vetoes of military-related bills. The incident remains a commonly cited example of backfired public relations.[48][49]

Dan Quayle

[edit]

One reason for Bush's choice of Senator Dan Quayle as his running mate was to appeal to younger Americans identified with the "Reagan Revolution." Quayle's looks were praised by Senator John McCain: "I can't believe a guy that handsome wouldn't have some impact."[50] But Quayle was not a seasoned politician, and made a number of embarrassing statements.[clarification needed] The Dukakis team attacked Quayle's credentials, saying he was "dangerously inexperienced to be first-in-line to the presidency."[51]

During the vice presidential debate, Quayle attempted to dispel such allegations by comparing his experience with that of pre-1960 John F. Kennedy, who had also been a young politician when running for the presidency (Kennedy had served 13 years in Congress to Quayle's 12). Quayle said, "I have as much experience in the Congress as Jack Kennedy did when he sought the presidency." "Senator, I served with Jack Kennedy. I knew Jack Kennedy," Dukakis's running mate, Lloyd Bentsen, responded. "Jack Kennedy was a friend of mine. Senator, you're no Jack Kennedy."[52]

Quayle responded, "That was really uncalled for, Senator," to which Bentsen said, "You are the one that was making the comparison, Senator, and I'm one who knew him well. And frankly I think you are so far apart in the objectives you choose for your country that I did not think the comparison was well-taken."

Democrats replayed Quayle's reaction to Bentsen's comment in subsequent ads as an announcer intoned, "Quayle: just a heartbeat away." Despite much press about the Kennedy comments, this did not reduce Bush's lead in the polls. Quayle had sought to use the debate to criticize Dukakis as too liberal rather than go point for point with the more seasoned Bentsen. Bentsen's attempts to defend Dukakis received little recognition, with greater attention on the Kennedy comparison.

Jennifer Fitzgerald and Donna Brazile firing

[edit]During the course of the campaign, Dukakis fired his deputy field director Donna Brazile after she spread unsubstantiated rumors that Bush had had an affair with his assistant Jennifer Fitzgerald.[53] Bush and Fitzgerald's relationship was briefly rehashed in the 1992 campaign.[54][55]

Presidential debates

[edit]There were two presidential debates and one vice-presidential debate.[56]

Voters were split as to who won the first presidential debate.[57] Bush improved in the second debate. Before the second debate, Dukakis had been suffering from the flu and spent much of the day in bed. His performance was generally seen as poor and played to his reputation of being intellectually cold. Reporter Bernard Shaw opened the debate by asking Dukakis whether he would support the death penalty if Kitty Dukakis were raped and murdered; Dukakis said "no" and discussed the statistical ineffectiveness of capital punishment. Some commentators thought the question itself was unfair, in that it injected an overly emotional element into the discussion of a policy issue, but many observers felt Dukakis's answer lacked the normal emotions one would expect of a person talking about a loved one's rape and murder.[58] Tom Brokaw of NBC reported on his October 14 newscast, "The consensus tonight is that Vice President George Bush won last night's debate and made it all the harder for Governor Michael Dukakis to catch and pass him in the 25 days remaining. In all of the Friday morning quarterbacking, there was common agreement that Dukakis failed to seize the debate and make it his night."[59]

| No. | Date | Host | Location | Panelists | Moderator | Participants | Viewership (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Sunday, September 25, 1988 | Wake Forest University | Winston-Salem, North Carolina | John Mashek Peter Jennings Anne Groer |

Jim Lehrer | Vice President George H. W. Bush Governor Michael Dukakis |

65.1[56] |

| VP | Wednesday, October 5, 1988 | Omaha Civic Auditorium | Omaha, Nebraska | Tom Brokaw Jon Margolis Brit Hume |

Judy Woodruff | Senator Dan Quayle Senator Lloyd Bentsen |

46.9[56] |

| P2 | Thursday, October 13, 1988 | University of California, Los Angeles | Los Angeles, California | Andrea Mitchell Ann Compton Margaret Warner |

Bernard Shaw | Vice President George H. W. Bush Governor Michael Dukakis |

67.3[56] |

Polling

[edit]| Poll source | Date(s) administered |

Sample size |

Margin of error |

George Bush (R) |

Michael Dukakis (D) |

Other | Undecided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New York Times/CBS News | May 9–12, 1988 | 1,056 RV | ± % | 39% | 49% | — | — |

| Gallup | June 24–26, 1988 | 1,056 RV | ± 3% | 41% | 46% | — | — |

| New York Times/CBS News | July 8–10, 1988 | 1,002 RV | ± % | 41% | 47% | — | — |

| July 18–21: Democratic National Convention | |||||||

| Gallup | July 21–22, 1988 | 948 RV | ± 4% | 38% | 55% | — | — |

| August 15–18: Republican National Convention | |||||||

| Wall Street Journal/NBC News | August 20–22, 1988 | 1,762 RV | ± 3% | 44% | 39% | — | — |

| Gallup | September 9–14, 1988 | 2,001 RV | ± % | 50% | 44% | — | — |

| ABC News/Washington Post | September 14–19, 1988 | 1,271 LV | ± 3% | 50% | 46% | — | — |

| NBC News/Wall Street Journal | September 16–19, 1988 | 2,630 RV | ± 2% | 45% | 41% | — | — |

| Sep. 25: Presidential debate | |||||||

| Gallup | September 27–28, 1988 | 1,020 RV | ± 3% | 47% | 42% | — | — |

| Oct. 13: Presidential debate | |||||||

| NBC News/Wall Street Journal | October 14–16, 1988 | 1,378 LV | ± 3% | 55% | 38% | — | — |

| NBC News/Wall Street Journal | October 23–26, 1988 | 1,285 LV | ± 4% | 51% | 42% | — | — |

Results

[edit]

In the November 8 election, Bush won a majority of the popular vote and the Electoral College.[60] Neither his popular vote percentage (53.4%), his total electoral votes (426), nor his number of states won (40) have been surpassed in any subsequent presidential election. This is the most recent election whereby both major party candidates shared the same birth state, which in this case, was Massachusetts.

Like Reagan in 1980 and 1984, Bush performed very strongly among suburban voters, in areas such as the collar counties of Chicago (winning over 60% in DuPage and Lake counties), Philadelphia (sweeping the Main Line counties), Baltimore, Los Angeles (winning over 60% in the Republican bastions of Orange and San Diego counties) and New York. As of 2020, Bush is the last Republican to win the heavily suburban states of California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, and New Jersey. He is also the last Republican candidate to win rural Vermont, which was historically Republican but by this time shifting away from the party, as well as the last Republican candidate to win Maine in its entirety, though Donald Trump won one electoral vote from the state in 2016, 2020, and 2024. Bush lost New York state by just over 4%. Bush is the first Republican to win the presidency without Iowa. In contrast to the suburbs, a solidly Republican constituency, Bush received a significantly lower level of support than Reagan in rural regions. Farm states had fared poorly during the Reagan administration, and Dukakis was the beneficiary.[61][62] This is the last election where Michigan and Pennsylvania voted Republican until 2016, New Mexico until 2004, and Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Tennessee until 2000. This is the last election where no state was decided by a margin under 1%.[63]

In Illinois, Bush lost a number of downstate counties that previously went for Reagan, and he lost Iowa by a wide margin, even losing in traditionally Republican areas. Bush also performed weaker in Missouri's northern counties, narrowly winning that state. In three typically solid Republican states, Kansas, South Dakota, and Montana, the vote was much closer than usual. The rural state of West Virginia, though not an agricultural economy, narrowly flipped back into the Democratic column. As of 2025, this is the only election since 1916 where Blaine County, Montana did not vote for the winning candidate.[64]

Bush performed strongest in the South and West. Despite Bentsen's presence on the Democratic ticket, Bush won Texas by 12 points. He lost the states of the Pacific Northwest but narrowly held California in the Republican column for the sixth straight time. As of 2025, this was the last election in which the Republican candidate won the support of a majority or plurality of women voters.[65]

Electoral results

[edit]| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| George H. W. Bush | Republican | Texas | 48,886,597 | 53.37% | 426 | Dan Quayle | Indiana | 426 |

| Michael Dukakis | Democratic | Massachusetts | 41,809,476 | 45.65% | 111 | Lloyd Bentsen | Texas | 111 |

| Lloyd Bentsen | Democratic | Texas | —(a) | —(a) | 1 | Michael Dukakis | Massachusetts | 1 |

| Ron Paul | Libertarian | Texas | 431,750 | 0.47% | 0 | Andre Marrou | Alaska | 0 |

| Lenora Fulani | New Alliance | Pennsylvania | 217,221 | 0.24% | 0 | —(b) | — | 0 |

| Other | 249,642 | 0.27% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 91,594,686 | 100% | 538 | 538 | ||||

| Needed to win | 270 | 270 | ||||||

Source (popular vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved August 7, 2005., Leip, David. "1988 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved August 7, 2005.

Source (electoral vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved August 7, 2005.

(a) West Virginia faithless elector Margarette Leach voted for Bentsen as president and Dukakis as vice president in order to make a statement against the U.S. Electoral College.

(b) Fulani's running mate varied from state to state.[66] Among the six vice presidential candidates were Joyce Dattner, Harold Moore,[67] and Wynonia Burke.[68]

Results by state

[edit]| States/districts won by Dukakis/Bentsen | |

| States/districts won by Bush/Quayle | |

| † | At-large results (Maine used the Congressional District Method) |

| Source:[69] | George H.W. Bush Republican |

Michael Dukakis Democratic |

Ron Paul Libertarian |

Lenora Fulani New Alliance |

Margin | State Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | |

| Alabama | 9 | 815,576 | 59.17 | 9 | 549,506 | 39.86 | – | 8,460 | 0.61 | – | 3,311 | 0.24 | – | 266,070 | 19.30 | 1,378,476 | AL |

| Alaska | 3 | 119,251 | 59.59 | 3 | 72,584 | 36.27 | – | 5,484 | 2.74 | – | 1,024 | 0.51 | – | 46,667 | 23.32 | 200,116 | AK |

| Arizona | 7 | 702,541 | 59.95 | 7 | 454,029 | 38.74 | – | 13,351 | 1.14 | – | 1,662 | 0.14 | – | 248,512 | 21.21 | 1,171,873 | AZ |

| Arkansas | 6 | 466,578 | 56.37 | 6 | 349,237 | 42.19 | – | 3,297 | 0.40 | – | 2,161 | 0.26 | – | 117,341 | 14.18 | 827,738 | AR |

| California | 47 | 5,054,917 | 51.13 | 47 | 4,702,233 | 47.56 | – | 70,105 | 0.71 | – | 31,180 | 0.32 | – | 352,684 | 3.57 | 9,887,064 | CA |

| Colorado | 8 | 728,177 | 53.06 | 8 | 621,453 | 45.28 | – | 15,482 | 1.13 | – | 2,539 | 0.19 | – | 106,724 | 7.78 | 1,372,394 | CO |

| Connecticut | 8 | 750,241 | 51.98 | 8 | 676,584 | 46.87 | – | 14,071 | 0.97 | – | 2,491 | 0.17 | – | 73,657 | 5.10 | 1,443,394 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 139,639 | 55.88 | 3 | 108,647 | 43.48 | – | 1,162 | 0.47 | – | 443 | 0.18 | – | 30,992 | 12.40 | 249,891 | DE |

| D.C. | 3 | 27,590 | 14.30 | – | 159,407 | 82.65 | 3 | 554 | 0.29 | – | 2,901 | 1.50 | – | −131,817 | −68.34 | 192,877 | DC |

| Florida | 21 | 2,618,885 | 60.87 | 21 | 1,656,701 | 38.51 | – | 19,796 | 0.46 | – | 6,655 | 0.15 | – | 962,184 | 22.36 | 4,302,313 | FL |

| Georgia | 12 | 1,081,331 | 59.75 | 12 | 714,792 | 39.50 | – | 8,435 | 0.47 | – | 5,099 | 0.28 | – | 366,539 | 20.25 | 1,809,672 | GA |

| Hawaii | 4 | 158,625 | 44.75 | – | 192,364 | 54.27 | 4 | 1,999 | 0.56 | – | 1,003 | 0.28 | – | −33,739 | −9.52 | 354,461 | HI |

| Idaho | 4 | 253,881 | 62.08 | 4 | 147,272 | 36.01 | – | 5,313 | 1.30 | – | 2,502 | 0.61 | – | 106,609 | 26.07 | 408,968 | ID |

| Illinois | 24 | 2,310,939 | 50.69 | 24 | 2,215,940 | 48.60 | – | 14,944 | 0.33 | – | 10,276 | 0.23 | – | 94,999 | 2.08 | 4,559,120 | IL |

| Indiana | 12 | 1,297,763 | 59.84 | 12 | 860,643 | 39.69 | – | – | – | – | 10,215 | 0.47 | – | 437,120 | 20.16 | 2,168,621 | IN |

| Iowa | 8 | 545,355 | 44.50 | – | 670,557 | 54.71 | 8 | 2,494 | 0.20 | – | 540 | 0.04 | – | −125,202 | −10.22 | 1,225,614 | IA |

| Kansas | 7 | 554,049 | 55.79 | 7 | 422,636 | 42.56 | – | 12,553 | 1.26 | – | 3,806 | 0.38 | – | 131,413 | 13.23 | 993,044 | KS |

| Kentucky | 9 | 734,281 | 55.52 | 9 | 580,368 | 43.88 | – | 2,118 | 0.16 | – | 1,256 | 0.09 | – | 153,913 | 11.64 | 1,322,517 | KY |

| Louisiana | 10 | 883,702 | 54.27 | 10 | 734,281 | 44.06 | – | 4,115 | 0.25 | – | 2,355 | 0.14 | – | 166,242 | 10.21 | 1,628,202 | LA |

| Maine † | 2 | 307,131 | 55.34 | 2 | 243,569 | 43.88 | – | 2,700 | 0.49 | – | 1,405 | 0.25 | – | 63,562 | 11.45 | 555,035 | ME |

| Maine-1 | 1 | 169,292 | 56.36 | 1 | 131,078 | 43.64 | – | Unknown | Unknown | – | Unknown | Unknown | – | 38,214 | 12.72 | 300,370 | ME1 |

| Maine-2 | 1 | 137,839 | 55.06 | 1 | 112,491 | 44.94 | – | Unknown | Unknown | – | Unknown | Unknown | – | 25,348 | 10.12 | 250,330 | ME2 |

| Maryland | 10 | 876,167 | 51.11 | 10 | 826,304 | 48.20 | – | 6,748 | 0.39 | – | 5,115 | 0.30 | – | 49,863 | 2.91 | 1,714,358 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 13 | 1,194,644 | 45.38 | – | 1,401,406 | 53.23 | 13 | 24,251 | 0.92 | – | 9,561 | 0.36 | – | −206,762 | −7.85 | 2,632,805 | MA |

| Michigan | 20 | 1,965,486 | 53.57 | 20 | 1,675,783 | 45.67 | – | 18,336 | 0.50 | – | 2,513 | 0.07 | – | 289,703 | 7.90 | 3,669,163 | MI |

| Minnesota | 10 | 962,337 | 45.90 | – | 1,109,471 | 52.91 | 10 | 5,109 | 0.24 | – | 1,734 | 0.08 | – | −147,134 | −7.02 | 2,096,790 | MN |

| Mississippi | 7 | 557,890 | 59.89 | 7 | 363,921 | 39.07 | – | 3,329 | 0.36 | – | 2,155 | 0.23 | – | 193,969 | 20.82 | 931,527 | MS |

| Missouri | 11 | 1,084,953 | 51.83 | 11 | 1,001,619 | 47.85 | – | – | – | – | 6,656 | 0.32 | – | 83,334 | 3.98 | 2,093,228 | MO |

| Montana | 4 | 190,412 | 52.07 | 4 | 168,936 | 46.20 | – | 5,047 | 1.38 | – | 1,279 | 0.35 | – | 21,476 | 5.87 | 365,674 | MT |

| Nebraska | 5 | 398,447 | 60.15 | 5 | 259,646 | 39.20 | – | 2,536 | 0.38 | – | 1,743 | 0.26 | – | 138,801 | 20.96 | 662,372 | NE |

| Nevada | 4 | 206,040 | 58.86 | 4 | 132,738 | 37.92 | – | 3,520 | 1.01 | – | 835 | 0.24 | – | 73,302 | 20.94 | 350,067 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 281,537 | 62.49 | 4 | 163,696 | 36.33 | – | 4,502 | 1.00 | – | 790 | 0.18 | – | 117,841 | 26.16 | 450,525 | NH |

| New Jersey | 16 | 1,743,192 | 56.24 | 16 | 1,320,352 | 42.60 | – | 8,421 | 0.27 | – | 5,139 | 0.17 | – | 422,840 | 13.64 | 3,099,553 | NJ |

| New Mexico | 5 | 270,341 | 51.86 | 5 | 244,497 | 46.90 | – | 3,268 | 0.63 | – | 2,237 | 0.43 | – | 25,844 | 4.96 | 521,287 | NM |

| New York | 36 | 3,081,871 | 47.52 | – | 3,347,882 | 51.62 | 36 | 12,109 | 0.19 | – | 15,845 | 0.24 | – | −266,011 | −4.10 | 6,485,683 | NY |

| North Carolina | 13 | 1,237,258 | 57.97 | 13 | 890,167 | 41.71 | – | 1,263 | 0.06 | – | 5,682 | 0.27 | – | 347,091 | 16.26 | 2,134,370 | NC |

| North Dakota | 3 | 166,559 | 56.03 | 3 | 127,739 | 42.97 | – | 1,315 | 0.44 | – | 396 | 0.13 | – | 38,820 | 13.06 | 297,261 | ND |

| Ohio | 23 | 2,416,549 | 55.00 | 23 | 1,939,629 | 44.15 | – | 11,989 | 0.27 | – | 12,017 | 0.27 | – | 476,920 | 10.85 | 4,393,699 | OH |

| Oklahoma | 8 | 678,367 | 57.93 | 8 | 483,423 | 41.28 | – | 6,261 | 0.53 | – | 2,985 | 0.25 | – | 194,944 | 16.65 | 1,171,036 | OK |

| Oregon | 7 | 560,126 | 46.61 | – | 616,206 | 51.28 | 7 | 14,811 | 1.23 | – | 6,487 | 0.54 | – | −56,080 | −4.67 | 1,201,694 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 25 | 2,300,087 | 50.70 | 25 | 2,194,944 | 48.39 | – | 12,051 | 0.27 | – | 4,379 | 0.10 | – | 105,143 | 2.32 | 4,536,251 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 177,761 | 43.93 | – | 225,123 | 55.64 | 4 | 825 | 0.20 | – | 280 | 0.07 | – | −47,362 | −11.71 | 404,620 | RI |

| South Carolina | 8 | 606,443 | 61.50 | 8 | 370,554 | 37.58 | – | 4,935 | 0.50 | – | 4,077 | 0.41 | – | 235,889 | 23.92 | 986,009 | SC |

| South Dakota | 3 | 165,415 | 52.85 | 3 | 145,560 | 46.51 | – | 1,060 | 0.34 | – | 730 | 0.23 | – | 19,855 | 6.34 | 312,991 | SD |

| Tennessee | 11 | 947,233 | 57.89 | 11 | 679,794 | 41.55 | – | 2,041 | 0.12 | – | 1,334 | 0.08 | – | 267,439 | 16.34 | 1,636,250 | TN |

| Texas | 29 | 3,036,829 | 55.95 | 29 | 2,352,748 | 43.35 | – | 30,355 | 0.56 | – | 7,208 | 0.13 | – | 684,081 | 12.60 | 5,427,410 | TX |

| Utah | 5 | 428,442 | 66.22 | 5 | 207,343 | 32.05 | – | 7,473 | 1.16 | – | 455 | 0.07 | – | 221,099 | 34.17 | 647,008 | UT |

| Vermont | 3 | 124,331 | 51.10 | 3 | 115,775 | 47.58 | – | 1,003 | 0.41 | – | 205 | 0.08 | – | 8,556 | 3.52 | 243,333 | VT |

| Virginia | 12 | 1,309,162 | 59.74 | 12 | 859,799 | 39.23 | – | 8,336 | 0.38 | – | 14,312 | 0.65 | – | 449,363 | 20.50 | 2,191,609 | VA |

| Washington | 10 | 903,835 | 48.46 | – | 933,516 | 50.05 | 10 | 17,240 | 0.92 | – | 3,520 | 0.19 | – | −29,681 | −1.59 | 1,865,253 | WA |

| West Virginia | 6 | 310,065 | 47.46 | – | 341,016 | 52.20 | 5 | – | – | – | 2,230 | 0.34 | – | −30,951 | −4.74 | 653,311 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 11 | 1,047,499 | 47.80 | – | 1,126,794 | 51.41 | 11 | 5,157 | 0.24 | – | 1,953 | 0.09 | – | −79,295 | −3.62 | 2,191,608 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | 106,867 | 60.53 | 3 | 67,113 | 38.01 | – | 2,026 | 1.15 | – | 545 | 0.31 | – | 39,754 | 22.52 | 176,551 | WY |

| TOTALS: | 538 | 48,886,597 | 53.37 | 426 | 41,809,476 | 45.65 | 111 | 431,750 | 0.47 | – | 217,221 | 0.24 | – | 7,077,121 | 7.73 | 91,594,686 | US |

Maine allowed its electoral votes to be split between candidates. Two electoral votes were awarded to the winner of the statewide race and one electoral vote to the winner of each congressional district. Bush won all four votes. This was the last election in which Nebraska awarded its electors in a winner-take-all format before switching to the congressional district method.[70]

States that flipped from Republican to Democratic

[edit]Close states

[edit]States with margin of victory less than 5% (195 electoral votes)

- Washington, 1.59% (29,681 votes)

- Illinois, 2.09% (94,999 votes)

- Pennsylvania, 2.31% (105,143 votes)

- Maryland, 2.91% (49,863 votes)

- Vermont, 3.52% (8,556 votes)

- California, 3.57% (352,684 votes)

- Wisconsin, 3.61% (79,295 votes)

- Missouri, 3.98% (83,334 votes)

- New York, 4.10% (266,011 votes)

- Oregon, 4.67% (56,080 votes)

- West Virginia, 4.74% (30,951 votes)

- New Mexico, 4.96% (25,844 votes)

States with margin of victory between 5% and 10% (70 electoral votes):

- Connecticut, 5.11% (73,657 votes)

- Montana, 5.87% (21,476 votes)

- South Dakota, 6.34% (19,855 votes)

- Minnesota, 7.01% (147,134 votes)

- Colorado, 7.78% (106,724 votes)

- Massachusetts, 7.85% (206,762 votes)

- Michigan, 7.90% (289,703 votes) (tipping point state)

- Hawaii, 9.52% (33,739 votes)

Statistics

[edit]Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

- Jackson County, Kentucky 85.16%

- Madison County, Idaho 84.87%

- Ochiltree County, Texas 83.25%

- Blaine County, Nebraska 82.24%

- Thomas County, Nebraska 82.19%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

- Starr County, Texas 84.74%

- Zavala County, Texas 84.02%

- Washington, D.C. 82.65%

- Duval County, Texas 81.95%

- Brooks County, Texas 81.94%

Maps

[edit]-

Results by congressional district, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

-

Election results by county.

-

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

-

County swing from 1984 to 1988

Voter demographics

[edit]| The 1988 presidential vote by demographic subgroup | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic subgroup | Dukakis | Bush | % of total vote | |||

| Total vote | 46 | 53 | 100 | |||

| Ideology | ||||||

| Liberals | 81 | 18 | 20 | |||

| Moderates | 51 | 49 | 45 | |||

| Conservatives | 19 | 81 | 33 | |||

| Party | ||||||

| Democrats | 83 | 17 | 37 | |||

| Republicans | 8 | 92 | 35 | |||

| Independents | 42 | 56 | 26 | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 42 | 57 | 48 | |||

| Women | 49 | 50 | 52 | |||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 40 | 59 | 85 | |||

| Black | 89 | 11 | 10 | |||

| Hispanic | 69 | 30 | 3 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| 18–29 years old | 47 | 53 | 20 | |||

| 30–44 years old | 46 | 54 | 35 | |||

| 45–59 years old | 42 | 58 | 22 | |||

| 60 and older | 49 | 51 | 22 | |||

| Family income | ||||||

| Under $12,500 | 63 | 37 | 12 | |||

| $12,500–25,000 | 43 | 56 | 20 | |||

| $25,000–35,000 | 43 | 56 | 20 | |||

| $35,000–50,000 | 42 | 57 | 20 | |||

| $50,000–100,000 | 38 | 61 | 19 | |||

| Over $100,000 | 33 | 66 | 5 | |||

| Region | ||||||

| East | 49 | 50 | 25 | |||

| Midwest | 47 | 52 | 28 | |||

| South | 41 | 59 | 28 | |||

| West | 46 | 53 | 19 | |||

| Union households | ||||||

| Union | 57 | 43 | 25 | |||

Source: CBS News and The New York Times exit poll from the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research (11,645 surveyed)[71]

See also

[edit]- 1988 United States House of Representatives elections

- 1988 United States Senate elections

- 1988 United States gubernatorial elections

- History of the United States (1991–2008)

- Al Gore 1988 presidential campaign

- Inauguration of George H. W. Bush

Notes

[edit]- ^ A faithless Democratic elector voted for Bentsen for president and Dukakis for vice president.

- ^ Maine's 2nd Congressional District has voted Republican in every election beginning in 2016, however Bush remains the last Republican to carry the state as a whole

References

[edit]- ^ "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press. Archived from the original on November 14, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Electoral College's Stately Landslide Sends Bush and Quayle Into History Archived August 1, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, December 20, 1988

- ^ Enten, Harry (December 26, 2022). "The most underdiscussed fact of the 2022 election: how historically close it was". CNN. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ Brownstein, Ronald (September 16, 2024). "Why these three states are the most consistent tipping point in American politics". CNN. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ "Bush Announces Quest for Presidency". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. October 13, 1987. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "Dole announces presidential hopes in hometown talk". Star-News. November 10, 1987. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "Robertson announces". Ellensburg Daily Record. October 2, 1987. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "Kemp announces bid for nomination". The Bryan Times. April 6, 1987. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Dionne, E. J. Jr. (September 17, 1986). "DU PONT ENTERS THE G.O.P. RACE FOR PRESIDENT". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "Haig announces his bid for presidency". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. March 24, 1987. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Wallace, David (August 6, 1987). "GOP PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE MAKES STOP IN SOUTH FLORIDA". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Witt, Evans (April 29, 1987). "Laxalt announces bid for presidency, says 'there is unfinished work to do'". Gettysburg Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "Rumsfeld enters race". The Telegraph-Herald. January 20, 1987. Archived from the original on November 21, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "Stassen Enters G.O.P. Race as 'Peace Candidate'". The New York Times. November 15, 1967. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 13, 2024. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ Dillin, John (February 18, 1988). "Even with win, Bush seen to be vulnerable". Christian Science Monitor. p. 1.

- ^ Oreskes, Michael; Times, Special To the New York (July 31, 1988). "Jackson Delivers a Speech, And He Mentions Dukakis (Published 1988)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 13, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Toner, Robin; Times, Special To the New York (June 17, 1988). "Dukakis, Backed by Gore, Vows to Contest the South (Published 1988)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c Dionne, E. J. Jr. (June 8, 1988). "CALIFORNIA AND JERSEY PUSH DUKAKIS OVER TOP AS DEMOCRATS' NOMINEE (Published 1988)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c Dionne, E. J. Jr. (June 9, 1988). "PRESIDENT ASSERTS DUKAKIS DISTORTS ECONOMIC PICTURE (Published 1988)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ "Washington Talk: Briefing; Getting Tough (Published 1988)". The New York Times. January 26, 1988. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Dowd, Maureen; Times, Special To the New York (August 27, 1987). "Prince Charming Candidate: So Far, a Democratic Fable (Published 1987)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ "Traficant of Ohio Planning Regional Presidential Effort (Published 1987)". The New York Times. November 1, 1987. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Wilkinson, D.A. (December 4, 1987). "Traficant hat tossed into ring". The Vindicator. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Toner, Robin; Times, Special To the New York (June 23, 1988). "Dukakis Avoids Taking a Stand On No. 2 Post (Published 1988)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Walter Mondale: Learning to Live With Fritz Archived October 21, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Rolling Stone. March 1, 1984.

- ^ Steve Neal for the Chicago Tribune. April 26, 1985. Democrats Think They See A Better Horse For '88 Race Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Dillin for The Christian Science Monitor. February 23, 1987 Cuomo's 'no' opens door for dark horses Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ E. J. Dionne Jr. (May 3, 1987). "Gary Hart The Elusive Front-Runner". The New York Times, pg. SM28. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Johnston, David; King, Wayne; Nordheimer, Jon (May 9, 1987). "Courting Danger: The Fall Of Gary Hart". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "The Gary Hart Story: How It Happened". The Miami Herald. May 10, 1987. Archived from the original on August 24, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ Warren Weaver, Jr. for The New York Times. September 29, 1987 Schroeder, Assailing 'the System,' Decides Not to Run for President Archived September 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bob Drogin for the Los Angeles Times. December 16, 1987 Hart Back in Race for President : Political World Stunned, Gives Him Little Chance

- ^ Associated Press, in the Los Angeles Times. March 13, 1988 Quits Campaign : 'The People 'Have Decided,' Hart Declares Archived February 28, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dowd, Maureen (September 12, 1987). "Biden's Debate Finale: An Echo From Abroad". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ Washington Post: Joseph Biden's Plagiarism; Michael Dukakis's 'Attack Video' – 1988. Archived January 31, 2011, at the Wayback Machine 1988.

- ^ "Professional Board Clears Biden In Two Allegations of Plagiarism". The New York Times. May 29, 1989. p. 29. Archived from the original on July 7, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Oates, Marylouise (July 22, 1988). "It Was the Speech That Ate Atlanta". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Golshan, Tara (July 26, 2016). "Bill Clinton's first major appearance at a convention almost destroyed his career". Vox. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ Lenora Fulani bio Archived February 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Speakers Platform. Retrieved February 20, 2006

- ^ Hoffman, David (June 10, 1988). "Bush Attacks Dukakis As Tax-Raising Liberal; Candidate Uses Spirited Speech To Draw His Battle Lines". Washington Post.

- ^ Dowd, Maureen (June 11, 1988). "Bush Traces How Yale Differs From Harvard". The New York Times. p. 10. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Baker, Russell (June 15, 1988). "The Ivy Hayseed". The New York Times. p. A31. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "Commercials - 1988 - Harbor". Livingroomcandidate.org. Archived from the original on March 22, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "Commercials - 1988 - Willie Horton". Livingroomcandidate.org. Archived from the original on July 13, 2024. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "Kitty Dukakis denies flag burning protest". The Bulletin. Bend, OR. August 26, 1988. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ Lauter, David (August 4, 1988). "Reagan Remark Spurs Dukakis Health Report". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Bradlee, Ben Jr.; Fred Kaplan (September 14, 1988). "Dukakis spells out Soviet policy". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Safire, William (September 15, 1988). "Rat-Tat-Tatting". The New York Times. p. A35. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Dowd, Maureen (September 17, 1988). "Bush Talks of Lasers and Bombers". The New York Times. p. 8. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Mapes, Jeff (August 17, 1988). "Bush taps Quayle for VP". The Oregonian. p. A01.

- ^ Toner, Robin (October 7, 1988). "Quayle Reflects Badly on Bush, Dukakis Asserts". The New York Times. p. B6. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "You're No Jack Kennedy Video". The History Channel. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ^ Sanders, Joshunda (July 4, 2004). "State's Dems still hope for a bit of suspense / A contested primary is viewed as a plus for party". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ Conason, Joe (July/August 1992). "Reason No. 1 Not To Vote For George Bush: He Cheats on His Wife." Spy magazine.

- ^ Kurtz, Howard (August 12, 1992). "Bush Angrily Denounces Report of Extramarital Affair as 'a Lie'". Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d "CPD: 1988 Debates". www.debates.org. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ After The Debate; Round One Undecisive Archived March 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine [sic] Dionne, E.J. New York Times. September 27, 1988.

- ^ Hirshson, Paul (October 19, 1988). "Editors on Dukakis: Down, but not out". The Boston Globe. p. 29. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016.

- ^ Death Penalty, Dan Quayle Are Subjects of Bush-Dukakis Debate Archived December 10, 2019, at the Wayback Machine NBC Nightly News. October 14, 1988. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ Leip, David (2012). "1988 Presidential General Election Results". Us Elections Atlas. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ^ Piliawsky, Monte (1989). "Racial Politics in the 1988 Presidential Election". The Black Scholar. 20 (1): 30–37. doi:10.1080/00064246.1989.11412915. ISSN 0006-4246. JSTOR 41068311.

- ^ Cohn, Peter (April 9, 2019). "This Iowa farmer has his finger on the 2020 pulse". Archived from the original on October 17, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Woodall, Candy (November 8, 2016). "Trump in huge upset becomes first Republican to win Pa. since 1988". Archived from the original on September 11, 2024. Retrieved September 11, 2024.

- ^ The Political Graveyard; Blaine County, Montana Archived October 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Election Polls -- Presidential Vote by Groups". Gallup.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Athitakis, Mark (August 11, 1999). "Booty Call". SF Weekly. Village Voice Media. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2006.

- ^ Fulani, Lenora (1992). The Making of a Fringe Candidate. Castillo International. p. 127. ISBN 0-9628621-3-4.

- ^ "Political Party History in Alaska". Internet Archive copy of official website of Alaska Division of Elections. 2003. Archived from the original on July 1, 2004. Retrieved March 24, 2006.

- ^ a b "1988 Presidential General Election Data – National". Archived from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ Barone, Michael (June 1989). The Almanac of American Politics, 1990. Macmillan Inc. ISBN 978-0-89234-044-6.

- ^ "How Groups Voted in 1988". ropercenter.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Alexander, Herbert E. Financing the 1988 election (1991)

- Cramer, Richard Ben (1992). What It Takes: The Way to the White House. Penguin Random House LLC. ISBN 0679746498. online

- de la Garza, Rodolfo O., ed. From Rhetoric to Reality: Latino Politics in the 1988 Elections (1992)

- Didion, Joan (October 27, 1988). "Insider Baseball". The New York Review of Books. 35 (16). ISSN 0028-7504. (Later included in Didion's essay collections After Henry and Political Fictions)

- Drew, Elizabeth. Election Journal: Political Events of 1987-1988 (1989) online

- Fleegler, Robert L. (April 11, 2023). Brutal Campaign. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-7337-0.

- Germond, Jack W., and Jules Witcover. Whose Broad Stripes and Bright Stars? (1989), narrative by two famous reporters; online

- Gopoian, J. David (1993). "Images and issues in the 1988 presidential election". Journal of Politics. 55 (1): 151–66. doi:10.2307/2132233. JSTOR 2132233. S2CID 154580840.

- Guth, James L., and John C. Green, eds. The Bible and the Ballot Box: Religion and Politics in the 1988 Election. (1991)

- Johnstone, Andrew, and Andrew Priest, eds. US Presidential Elections and Foreign Policy: Candidates, Campaigns, and Global Politics from FDR to Bill Clinton (2017) pp 293–316. online

- Lemert, James B.; Elliott, William R.; Bernstein, James M.; Rosenberg, William L.; Nestvold, Karl J. (1991). News Verdicts, the Debates, and Presidential Campaigns. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-93758-5.

- Moreland, Laurence W.; Steed, Robert P.; Baker, Tod A. (1991). The 1988 Presidential Election in the South: Continuity Amidst Change in Southern Party Politics. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-93145-5.

- Pitney Jr., John J. After Reagan: Bush, Dukakis, and the 1988 Election (UP Kansas, 2019) excerpt

- Pomper, Gerald M., ed. The Election of 1988 : Reports and Interpretations (1989) online

- Runkel, David R. (1989). Campaign for President: The Managers Look at '88. Dover: Auburn House. ISBN 0-86569-194-0.

- Stempel, Guido H. III; Windhauser, John W. (1991). The Media in the 1984 and 1988 Presidential Campaigns. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-26527-5.

External links

[edit]- 1988 popular vote by counties

- 1988 popular vote by state

- 1988 popular vote by states (with bar graphs)

- Campaign commercials from the 1988 election

- Booknotes interview with Jack Germond and Jules Witcover on Whose Broad Stripes and Bright Stars? The Trivial Pursuit of the Presidency 1988, August 27, 1989.

- Booknotes interview with Arthur Grace on Choose Me: Portraits of a Presidential Race, December 10, 1989.

- Booknotes interview with Paul Taylor on See How They Run: Electing the President in an Age of Mediaocracy, November 4, 1990.

- Booknotes interview with Richard Ben Cramer on What It Takes: The Way to the White House, July 26, 1992

- Election of 1988 in Counting the Votes